Share Content

Article Link Copied

“Science And Research Never Stop To Change.”

As of April 2019, Nora Maria Raschle, PhD, joined the Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development at the University of Zurich as an Assistant Professor of Psychology. We spoke to Nora about her research plans, her own blog, and about communicating complex research results to society in a more understandable way.

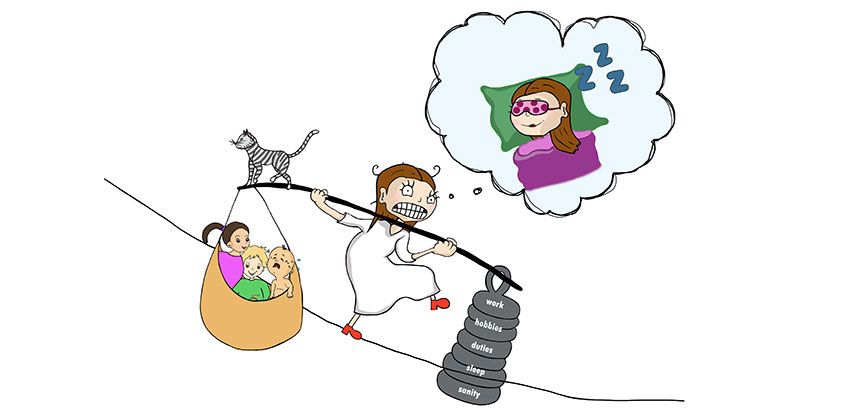

Nora, you are an accomplished scientist, a mother of three kids, and an avid science communicator and illustrator running your own blog www.bornascientist.com. Do you ever sleep?

*Laugh* Sometimes more, sometimes less. No different than most parents out there. For me, having more than one focus does in fact help balancing out my stress levels coming from the other areas. Keeping a good balance and mental health is important. Science, art and sports have always been a great passion of mine growing up. And from the moment our first kids were born, family has been the center of it all. Scientists are defined by their desire to create new knowledge, investigate questions and build new theories. In all other aspects they are and should be as diverse as humans gets.

Your interviews with fellow scientists on your blog often start with the question “how did you get into research”? So how did YOU get into research?

I have been blessed by being able to follow my passions in life. My parents supported me in studying STEM topics and I grew up with two brothers teaching me to stand my grounds, be it on the soccer field or in math college. I have always been an avid reader and been fascinated by how the human brain makes us work. My masters and PhD studies were shaped by the people I have met and the places I was able to travel to. Teachers like Prof. Lutz Jäncke at the University of Zurich instilled my hunger to learn more about the human brain. I was able to travel early on and completed my thesis with Prof. Gottfried Schlaug (Music and Neuroimaging Laboratory at the Beth Israel Deaconness Medical School and Harvard University in Boston; USA). During my predoctoral and postdoctoral studies in Prof. Nadine Gaab’s laboratory I had the opportunity to gain valuable insights into the developing human brain including all the methodological and practical challenges that come along with it and I was lucky to have an amazing female role model.

“I believe that any of our research efforts loses value, if a translation to society fails.” Nora Maria Raschle, PhD.

You are pursuing projects in the field of pediatric neuroimaging – in other words, you put fidgety little kids in the brain scanner. What is your secret to keep them entertained while in the scanner so that they hold still?

They are doing quite fine to be honest! Children are able to understand so much more than we sometimes expect them to. Young children are much more used than us to encounter novel situations on a daily basis. But it is true that staying still can be a challenge. We put a lot of emphasis on easy understandable communication, child-friendly research protocols with games, adventures, movies and colourful images for a better experience of all. There are many little tricks and if you are interested in learning more, you can also check out our video protocol “Making MR Imaging Child’s Play”.

Your blog aims at spreading knowledge in a way that is fun and easily understandable for everyone. You want to break down the walls raised by complicated communication. But sometimes science, scientific results, and particularly the implications aren’t that straightforward, are they?

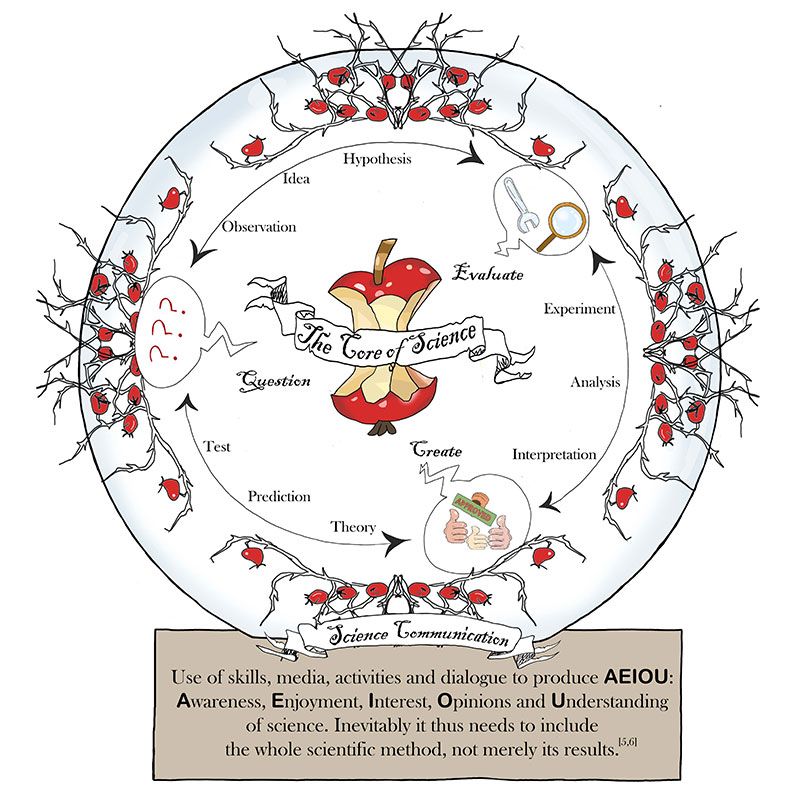

Successful science communication is an art for itself. It requires a careful translation, not just of the main scientific results, but also of the methods that have led to a specific conclusion. Illustration by Nora Maria Raschle.

Yes and no. The mere results as described in the corresponding section of a scientific article should be strictly descriptive and free of interpretation. In its discussion part, however, the researchers try to draw a bigger picture, embed their findings within the known literature and draw new conclusions and hypothesis. There are subtle ways to word such conclusions and the scientific jargon is not as straightforward to understand. Notably, the way that scientific articles are written is a foreign language to most. I believe that it is part of the researcher and Universities’ responsibility to find ways of communicating their findings in terms that can be understood by all.

Science communication consumes a lot of valuable time in the life of a researcher – time that could be put to good use for other endeavors such as writing scientific articles. Is it advisable for scientists early in their career to spend their time explaining their research to lay people or is this something best left to professors with tenure?

For one, I believe that being funded by the public we have a duty to support translational efforts and, secondly, scientist at any level of expertise can profit from participating in science communication. For example a student that is able to successfully explain their research in lay terms to another person has really understood the core of what they were doing. There is no hiding between complicated formulations and terminologies. There are many different forms of science communication, such as giving interviews, taking part in group discussions, giving TED talks, speeches, through audio ot art without boundaries to creativity.

What is it that fascinates you most about doing research?

Science and research are extremely lively areas of work, they never stop to change. I can go to work every day learning new things and studying what I am most fascinated about; the developing human brain. How this super complex organ grows, learns and changes. How it makes us unique. Although it comes with challenges too, science is an extremely rewarding field.

What is it that frustrates you most about doing research?

Ultimately anything you do with all your heart is prone to leading to some frustration eventually. Keeping a good balance and mental health are key. For academics, stress may come from the competitiveness in the research field, the continuous hunt towards obtaining sufficient funding, publishing enough and with large impact or obtaining visibility, all ultimate measures of institutional success. Rejection and failure are unavoidable in this process. Plus, there are limits to the systems. For example, predefined measures of what entails a successful application might ultimately overlook the most promising, novel, high-risk but cutting-edge project ideas. And finally, we still got various biases to overcome (e.g. publication, gender, etc.).

And finally, what is that you absolutely want to accomplish within the next 10 years?

Most importantly I want our family to be happy and for our children (8/8/4 years) to grow up to become happy and decent human beings.

Workwise, I aim to continue my research in the field of human brain development with the goal to provide towards (1) the characterization of typical and atypical behaviour in order to inform about health and disease, (2) the use of this knowledge for the early identification and characterization of those that struggle, (3) a final implementation of this to result in specific treatment, care or learning programs that can support those individuals in need. Ultimately, I aim to work towards an increase in acknowledgement, detection and prevention of early adversities and reduce the consequences that come along with these; whether they are caused by disease, disadvantage or heritage in order to give every child the same starting point in life.

I believe that any of our research efforts loses value, if a translation to society fails. It will be important that we will not only collect more or better research data, represent the individuals well and reach individual prediction levels; we will also have to work towards questions on how we can implement and translate the scientific findings in an effective way that is reaching clinical importance, political levels and educational systems.